Of course, if you think they’re the same thing, then that’s only one thing you can improve. But I don’t think they are, and I believe that understanding which should be the focus of each improvement project will enhance the project’s outcomes.

There is no doubt that in the post-COVID world (if indeed there is any such thing), law firms and other professional services firms are going to find their major clients will have less money to spend on professional services, even as their need for those services might well be growing.

“More for less” was clients’ prevailing demand post-credit crunch, and the firms’ response to it was a priority until about three years ago, when the legal tech bubble finally engulfed nearly all the work on process, efficiency, right-sizing etc.

Now we’re likely to be back there. And I think it’s vital this time around that we are able to quickly focus on the real problem. To do this will require some understanding of the difference between efficiency and productivity.

So, at the risk of being simplistic, let’s decompose “more for less” into two slightly (individually) less ambitious concepts – “more for the same”, and “the same for less”. The first describes productivity – how do I get more out what I’ve got? The second describes efficiency – how do I reduce the cost of the overall process of turning inputs into outputs?

Mathematically, there is one major difference between them. It probably to helps to look at the relationship between output and input as a fraction…

![]()

In trying to get output up, while holding input constant – the focus of productivity – there is theoretically no limit on the amount of output that can be produced – the limit is infinity. Given an unlimited demand for work, the increasingly productive lawyer can just do more of it.

But in trying to get inputs down while holding output constant – the focus of efficiency – the limit is zero. And as we get closer to zero, it becomes both harder to do and less worth doing. (It’s also why cost cutting is a game of diminishing returns.)

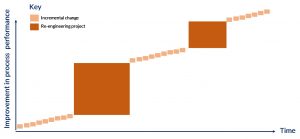

We’ve been doing explicit process improvement now for over a century (since Taylor and Ford in the early 20th century and certainly seriously since Deming in the 1930s/40s), and we’re chest-deep in methods and approaches, some of them attaining quasi-religious status.

So, some of our processes ought to be pretty well as good as they can be by now, short of the next technological innovation.

Thankfully, for those of us involved in process improvement work, there are still plenty of organisations out there that either haven’t made much effort to improve processes or are (inadvertently) implementing new inefficient processes.

Let’s briefly pause here for some stunning generalisations:

- Productivity – is about the individual lawyer, is key for the complex world of more bespoke matters, and suits the billable hour pricing model.

- Efficiency – is about the process/system, is key for the world of transactional law and repetitive matter types, and is a necessary focus in the fixed fee world.

So when we look at the way a particular matter type is performed by a firm (as I have spent a lot of time doing) , and we eventually decide that some of the work done today by a partner can be automated , or done by an associate with 5 years PQE, we are improving the efficiency of the matter process. The overall cost for the delivery of one instance of the matter type is reduced by:

- the difference in labour rates of partners and associates, or

- the cost savings from the use of technology.

Taken to its extremes (it hasn’t been yet), this replaces most of the partners in a firm with technology, or with associates, who are themselves eventually replaced by paralegals. The firm’s revenue drops accordingly and although profitability is improved, the absolute amount of profit is massively reduced.

This is what partners invited to participate in process mapping exercises always (and with occasional justification) describe as “the race to the bottom”, and never mind whether it works for the client.

Had we approached the same problem with the purpose of improving productivity, our focus would have been on the work of the partner, rather than on the whole process. In looking at what we really want our partners to do, we might well have come to the same conclusion that involvement in lower-order tasks was a barrier to the lawyer’s productivity, and could be hived off to an associate. But we might also have found all sorts of other things that inhibit partner productivity, such as time wasted in:

- firm procedures;

- firm management meetings;

- poorly organised business development activity;

- unproductive and ill thought-through client meetings;

- box-ticking supervision;

- a myriad of bureaucratic activities; and

- the partner’s own time management disciplines.

For a focus on productivity to be worthwhile there has to be an increasing amount of work. We may well be in the situation, short-term, where some types of work do increase. We will also be faced by clients demanding more for less. The worst situation will be where the absolute amount of work increases while the revenue from it spirals downwards.

And of course, at some point, the two concepts combine. In a world where increases in lawyer productivity outstrip the increase in external demand for those lawyers’ services, then at some point it makes sense to have at least one fewer lawyer. At a firm level, that’s an increase in productivity eventually translating into an increase in efficiency. But the focus of the improvement work will have been on the lawyers’ productivity, not on their individual efficiency.

But my real message is that most firms will need to address both productivity and efficiency, and will need a laser focus on, and honesty about, the type of work the firm is really doing, so that the right focus can be brought to bear on each matter type, or on each lawyer, being assessed. This might initially be harder than the improvement exercise itself, but it shouldn’t be, and with practice, won’t be. The key, as always, to getting the solution right, is to understand the problem properly.

Photo credits: documents icon (below) by Richard Copley; featured image (top) by Anete Lūsiņa on Unsplash